The Colorado Trail is a 471 mile hiking trail that stretches through the Colorado Rockies from Denver to Durango. It passes through seven national forests and six wilderness areas, crosses five rivers, and eight major mountain ranges. It is a hiker’s paradise. It is a trail of grandeur and uncommon beauty.

I first hiked part of it in the summer of 2002. I had talked my neighbor, Jeanne, into backpacking a section with me. We covered less than fifty miles, and it was, without a doubt, one of the best experiences of my life.

Immediately, we planned on returning and hiking more of the trail the following summer. One month before we were scheduled to leave, Jeanne was forced to cancel. The trip that I had spent countless hours planning and dreaming of was off.

At the time, my seventeen-year-old daughter, Scarlett, had nonchalantly said, “I’ll go with ya.” I smiled at her offer, but turned her down. She was a dancer, lean and strong, but she had not spent the last four months training with a loaded backpack on her back. I was afraid the combination of weight and elevation would be too much for her.

I quit training. I put my backpack in the closet.

Two weeks later, Scarlett and I were sitting next to each other in church. We were watching some sort of video on the large screen positioned at the front of the church. I don’t remember what the message was that day, or even what the video was about. But I do remember that occasional images of mountains flashed across the screen. As I sat there in the darkness, mountain scenes of waterfalls, streams, and meadows flashed before us. After a particularly breathtaking shot of a flower-studded meadow, I turned toward Scarlett and whispered, “Let’s go to Colorado.”

“Really?” she said, a wide smile spreading across her face.

I nodded. “Me and you.”

We began training the next day.

After adjusting my old backpack to fit her, we began training in a nearby state park. Although there were a few small hills within the boundaries of the park, there was no way that we could duplicate the conditions that we would face in Rocky Mountains. The best that we could hope for was to strengthen our legs and build our weight carrying capacity.

After adjusting my old backpack to fit her, we began training in a nearby state park. Although there were a few small hills within the boundaries of the park, there was no way that we could duplicate the conditions that we would face in Rocky Mountains. The best that we could hope for was to strengthen our legs and build our weight carrying capacity.

When Jeanne and I had started training the previous year, we had started by carrying ten pounds in our backpacks. We gradually increased that by five pounds each week until we were each 40 pounds. Scarlett would have no such luxury. We started her with fifteen pounds the first day. She was at twenty-five by the end of the week. At thirty-five by the end of the following week. We had fourteen days to train. It rained four of those days. I told Scarlett that we needed to train, rain or not. She talked me out of it.

“Nah, we’ll be fine,” she reassured me.

“If it rains on the trail, we will have to hike. We won’t have a choice,” I told her.

The plan was for us to be dropped off at a designated spot, and then be picked up five days later at another designated spot, 45 miles away. If you are thinking nine miles a day doesn’t sound like much, you have never hiked the Rockies. We had a window of half an hour. Our ride would arrive fifteen minutes before our designated pick up time and wait fifteen minutes after. That was it. We had to cover an average of nine miles per day. Period. Rain or shine. I was worried about Scarlett’s ability to possibly hike for days in the rain. I was also worried about her ability to unquestioningly follow my directions. Of my three children, she is the one that I most often butt heads with, the one that knows exactly how to push my buttons, the one that is the most exasperating. She is unbelievably stubborn, always questions authority, never thinks before she speaks, and always has to have the last word. She is, exactly, like her mother.

“We’ll be fine,” she told me again. I looked into her blue eyes and hoped she was right.

Colorado was a nineteen hour drive from our Indiana home. The plan was to drive twelve hours the first day and seven hours the second day.

Unable to sleep, the night before we were to leave I stared at the dark ceiling, going over the contents of both of our backpacks. Wondering if we had enough clothing in our backpacks. Wondering if we had enough food. Wondering if I was crazy. Wondering if I was risking my daughter’s life by taking her into the wilderness and leading her over impossibly steep mountain trails, and through dense woods inhabited by bears and mountain lions. Imagining her slipping and falling off the side of a cliff.

Finally, I fell asleep a little after three.

The alarm went off at 3:45.

We pulled out of the driveway at 4:00, listening to the Dixie Chicks singing Wide Open Spaces, and headed west. My favorite direction.

I don’t know why the mountains beckon me as they do. I do know there is no place where I feel more at peace, more at home, more at one with the universe. The previous year, on my hike with Jeanne, she was asleep in the tent on our first night. I was standing outside, unable to sleep, full of mountain adrenaline, full of the knowledge that, at that very moment, I was living one of my dreams. We had pitched the tent in a meadow surrounded by mountains. It was dark, but I could still see the outline of the mountains against the star filled sky. I stood there, in that wilderness meadow, looking toward heaven, no one but Jeanne for miles and miles, and I felt a sensation that I had not felt before or since — as if I was being rocked in the lap of God. I felt no fear, no sense of danger. Only a total sense of contentment and peace — a certainty that, at that moment, I was exactly where I was supposed to be. This is the feeling I wanted to share with my daughter.

I don’t know why the mountains beckon me as they do. I do know there is no place where I feel more at peace, more at home, more at one with the universe. The previous year, on my hike with Jeanne, she was asleep in the tent on our first night. I was standing outside, unable to sleep, full of mountain adrenaline, full of the knowledge that, at that very moment, I was living one of my dreams. We had pitched the tent in a meadow surrounded by mountains. It was dark, but I could still see the outline of the mountains against the star filled sky. I stood there, in that wilderness meadow, looking toward heaven, no one but Jeanne for miles and miles, and I felt a sensation that I had not felt before or since — as if I was being rocked in the lap of God. I felt no fear, no sense of danger. Only a total sense of contentment and peace — a certainty that, at that moment, I was exactly where I was supposed to be. This is the feeling I wanted to share with my daughter.

I also love the challenge of backpacking in Colorado. Hiking in the Rockies is not for the faint hearted. The elevation alone is enough to, literally, leave you gasping. Furthermore, a misstep on a mountain slope, miles from civilization and without cell phone coverage, could be disastrous. There is also the very real possibility of getting lost. Although the Colorado Trail is identified sporadically with green and white triangular shaped markers, these markers can be miles apart, and, in between, there are other trails that cross, making the going confusing at times. In addition, above alpine level vegetation is scarce and there are no trees to post the markers. In these situations, piles of rocks (cairns) are used. Piles of rocks can fall over and can be difficult to spot atop a mountain made of the exact same rock. In such cases, a compass and topographical map are a necessity. It is into this environment — wild, savage, and heartbreakingly beautiful — that I was taking my daughter.

Somewhere in Iowa, eleven hours later, I wake Scarlett up to tell her she has slept for eight hours straight and that we should probably eat something for lunch. She is amazed that she has slept for so long. So am I. The trip is not going as I had planned. She has slept. I have changed cds. Trapt, Train, The Calling, Melissa Etheridge, Meat Loaf, Led Zeppelin, and Enrique. It’s an odd mix. So am I. I feel, so far, like I have been traveling alone. I imagined long talks as we drove, shared confidences, and some bad singing.

We opt for McDonalds, go inside to use the bathroom, and go back to the car for drive through. We eat as we drive. She is astonished that we have driven so far. “This trip is going by fast,” she tells me as she sticks a fry into her mouth. “We should just drive all the way through to Colorado.”

“Easy for you to say. You just slept eight hours.”

She laughs and takes a drink.

Cher is singing It’s In His Kiss. We sing along in between bites and I keep driving.

We drive through Nebraska at eighty miles per hour, five over the limit, past thousands and thousands of acres of corn and not one patrol car. We stop in Kearney. I had hoped to make it this far. We will eat somewhere and get a hotel for the night. Tomorrow, it will be a seven hour drive to Frisco, Colorado, just outside of Breckenridge. We drive past a strip of restaurants and can’t seem to agree on one.

We drive through Nebraska at eighty miles per hour, five over the limit, past thousands and thousands of acres of corn and not one patrol car. We stop in Kearney. I had hoped to make it this far. We will eat somewhere and get a hotel for the night. Tomorrow, it will be a seven hour drive to Frisco, Colorado, just outside of Breckenridge. We drive past a strip of restaurants and can’t seem to agree on one.

“Are you even hungry?” Scarlett asks.

“Not really.”

I look at her, thinking before I say the next sentence, already anticipating her response. “We could just eat drive through and keep driving.”

“How far?”

“To our hotel in Colorado.”

“Are you serious?”

“Yeah.”

“Could you do that? Keep driving that long?”

“We would have to do drive through, keep driving. Not waste any time.”

She smiles at me. “Let’s do it.”

I knew this would be her answer. Sometimes we bring out the worst in each other, but more often, we bring out the best.

We drive through Arby’s. And then through the rest of Nebraska. We pass one cornfield after another. The moon roof back, the widows down, the music loud. Me and my baby girl. It was perfect.

As we pass the Colorado state line John Denver is singing Rocky Mountain High. The next song will be I Guess He’d Rather Be In Colorado. In my car, there is no other way to enter Colorado. The eastern plains of Colorado are incredibly flat. It is not until we near Denver that the distant mountains come into view. It is a sight that never fails to move me. As we drive, the sun is setting behind the mountains. We point and laugh and smile. Beside us is a red jeep with California plates. In it are four guys and a girl — late teens, early twenties. Our vehicles are parallel and the seven of us all watch the sunset, exchanging smiles. Soon, one of the guys picks up a cell phone and points at it, wondering if we have one, too. Scarlett holds up a phone. He starts motioning to us, giving us their cell phone number. Scarlett starts repeating the numbers to me.

“Scarlett, we are not calling them.”

“Why? They seem nice. They look like surfers.” My daughter is an incredible beauty with long blonde hair and blue eyes. She is also sometimes as naïve as she is beautiful.

“Scarlett, we are not calling them,” I repeat.

The guy driving looks at me and smiles. I smile back and then laugh. I have tee shirts older than he is. The guy in the back is still trying to convey their number. Scarlett looks over at them, shrugs and smiles. I push on the gas and we pull away.

By the time we enter the mountains, a fine mist has begun to fall. The section of I-70 that we are traveling has just been freshly paved. It is very black, as is the night. There are no lines painted on the road yet. The rain is decreasing visibility. At this point, I have been driving for almost eighteen hours with only forty-five minutes of sleep the night before.

By the time we enter the mountains, a fine mist has begun to fall. The section of I-70 that we are traveling has just been freshly paved. It is very black, as is the night. There are no lines painted on the road yet. The rain is decreasing visibility. At this point, I have been driving for almost eighteen hours with only forty-five minutes of sleep the night before.

My eyes are heavy and I am struggling to keep them open. On either side of the road are two options, driving over a cliff or crashing into the sides of mountain. Normally, this is a section of road that excites me. It is officially “in” the mountains.

Scarlett is getting sleepy. I tell her she needs to stay awake. She needs to help me stay awake. She changes the cd to Bon Jovi and turns up the volume.

She also starts intently watching the road and the traffic. “Watch out for that truck, Mom.”

“I see him.”

“Are you okay?” she asks.

“Yeah, I’m okay.”

“Maybe we should stop.”

“There’s nowhere to stop here. We’re in the middle of the mountains. No hotel here. Another hour and we will be in Frisco. We’re okay.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yeah.” But I’m not so sure. My eyes burn and my lids are heavy. The rain worsens. The road twists through the mountains and there are points where I’m not sure how many lanes exist, three or four. There are no guardrails — a point that I have found, in the past, to be sort of cool. We don’t need no stinkin guardrails. At that moment, though, I’m not so sure. A bright white guardrail might be nice.

My eyes close for just a second. I feel gravel under the wheels and pull the car back onto the road.

“Mom, you okay?”

“Yeah, I’m fine,” I lie. I sit up straighter. Turn the heat down. Turn the volume up. Jon Bon Jovi sings about Tommy and Gina living on a prayer and I struggle to stay awake. Scarlett starts a non-stop stream of talk. She is relentless. She forces me to answer her, keeping me engaged in conversation. She is determined to keep me awake. That fact becomes apparent. A little over an hour later, we pull into the parking lot of the Best Western in Frisco, Colorado. Safe.

The next day we sleep in, have a late breakfast, grab our backpacks and drive to CopperMountain ski resort. The plan is to get in a little practice and become accustomed to the elevation before we start the actual hike. We park, strap the backpacks to our backs and walk through the resort area, past condos and restaurants and up-scale shops. We get some stares – this mother/daughter team donning backpacks, wearing hiking boots and both of us with our long hair pulled through baseball caps. I look at her and smile. Scarlett smiles back. We like this. We feel tough. Independent. Adventurous. And incredibly cool. We continue to make our way through the resort, past the base of the first ski lift, and onto a trail that climbs the mountain. Scarlett is in the lead. I decide to let her set the pace. I think it is a little fast, but say nothing. She is talking, non-stop, about everything and nothing, and I notice she is not even slightly winded. I am. We continue and I tell her she might want to slow down a little, pace herself. She says she is fine. I tell her we will take a break just ahead. She shrugs okay. We stop and I catch my breath. I am astonished at her ability to carry this weight with no visible effect.

The next day we sleep in, have a late breakfast, grab our backpacks and drive to CopperMountain ski resort. The plan is to get in a little practice and become accustomed to the elevation before we start the actual hike. We park, strap the backpacks to our backs and walk through the resort area, past condos and restaurants and up-scale shops. We get some stares – this mother/daughter team donning backpacks, wearing hiking boots and both of us with our long hair pulled through baseball caps. I look at her and smile. Scarlett smiles back. We like this. We feel tough. Independent. Adventurous. And incredibly cool. We continue to make our way through the resort, past the base of the first ski lift, and onto a trail that climbs the mountain. Scarlett is in the lead. I decide to let her set the pace. I think it is a little fast, but say nothing. She is talking, non-stop, about everything and nothing, and I notice she is not even slightly winded. I am. We continue and I tell her she might want to slow down a little, pace herself. She says she is fine. I tell her we will take a break just ahead. She shrugs okay. We stop and I catch my breath. I am astonished at her ability to carry this weight with no visible effect.

“I think I’ll be fine,” she tells me.

“You’re doing really well.” I have visions of myself not being able to keep up with her. Me — the one who has been training for the last four months! The thought is depressing. I have overestimated my abilities, underestimated hers. We continue another half an hour up the mountain and then turn to descend back into the resort. We spend the rest of the day exploring shops and restaurants in Breckenridge. This is our routine for the next three days. Hiking, shopping, eating, and trips to the hotel pool.

On the morning we are to start hiking the Colorado Trail we fill up our filtered water bottles from the hotel sink. “The next time we fill these, we will be dipping them into a creek,” I tell her.

Scarlett looks at me and, for the first time, I see apprehension in her eyes. “A creek?” she says with skepticism.

I nod.

She thinks about it for a minute. “What if we can’t find a creek?”

“We will.”

We carry our backpacks down the elevator and through the lobby. We are wished well by various hotel workers we have talked to over the past few days.

Our “shuttle service” is a guy named Eddie with a four wheel drive truck. Jeanne and I used his service the previous year. He has lived in Colorado all of his life. As we drive, he talks non-stop and tells stories of local characters, of ski trips, of his buddy the sherpa who was married last year and is now making his fifth trip to Everest as a guide.

I feel as I always do when I’m around these kind of people. As if I am missing out on life, as if, at times, I am just a waste of oxygen. It is almost an hour drive through breathtaking scenery to our drop off point. Scarlett is quiet. We exchange smiles occasionally during Eddie’s story telling.

He drops us off at a point where the Colorado Trail crosses a highway outside of Leadville. “See you in five days,” he tells us before pulling away. We pull our backpacks on, adjust them, and look at each other.

“You ready?” I ask her.

“Yep,” she answers.

“Let’s do it.”

We pass through a gate, cross a railroad track, and follow the trail through a long mountain meadow.

“So this is it?” she asks. “This is the Colorado Trail?”

“Yep, this is it.”

She laughs. “This is weird. It’s like, just you and me, out in the middle of nowhere.”

I look at her and smile. “Yeah,” I say with a huge smile.

The first few miles are incredibly easy and relatively flat. The path is padded by pine needles, and shade is over our heads as we make our way through a conifer forest. “This isn’t bad at all,” she tells me. “But I was hoping to get some sun.”

I laugh. “Enjoy it while you can. It won’t be like this for long.”

At this point, we run into another hiker. A guy of about nineteen or twenty who had just finished hiking the 2100 mile Appalachian Trail and was now hiking the Colorado Trail in its entirety. At his side was a thin and happy dog carrying its own backpack. I asked the hiker how he would compare the two trails. He said the preferred the Appalachian Trail. I was shocked. How could it compare to the grandeur of the Colorado Rockies? “No, it’s not that,” he told me. “The Rockies are prettier, but the AT is more social, has more people.”

I laughed. “That’s why I like this trail. Less people.”

He smiled. We wished him well, he did the same, and we continued in opposite directions.

Later that day, we begin our first ascent. The trail is in full sun, nothing but rock and compacted dirt under our feet, and relentlessly uphill. Scarlett is in the lead. I have decided to let her set the pace. Let her find her mountain legs. I follow her lead, despite the fact that I prefer to lead. As we ascend the mountain in earnest, her pace slows. I reassure her that the point is to keep moving, not to move fast. I tell her about the system that Jeanne and I worked out the year before. If either of us wanted to rest, we called out “break” and the other stopped — no questions asked, until we were able to continue. It was not long before she called out, “break.” We stood there, both of us struggling with the elevation gain, both of us gasping.

Later that day, we begin our first ascent. The trail is in full sun, nothing but rock and compacted dirt under our feet, and relentlessly uphill. Scarlett is in the lead. I have decided to let her set the pace. Let her find her mountain legs. I follow her lead, despite the fact that I prefer to lead. As we ascend the mountain in earnest, her pace slows. I reassure her that the point is to keep moving, not to move fast. I tell her about the system that Jeanne and I worked out the year before. If either of us wanted to rest, we called out “break” and the other stopped — no questions asked, until we were able to continue. It was not long before she called out, “break.” We stood there, both of us struggling with the elevation gain, both of us gasping.

“This is crazy,” she tells me.

“Yeah,” I nod. “But don’t you feel…I don’t know….alive?”

“No,” she laughs. “Closer to dead.”

We continue slowly up the mountain, zigzagging up switchbacks through boulders and gaining elevation. She tugs at her backpack straps occasionally. We stop for a couple adjustments, a few breaks, but other than that, she keeps going. She now moves at a steady pace. As we continue to gain elevation, each step becomes increasingly difficult. She has difficulty breathing, as do I, but she continues. Behind her, I focus on the ground, the back of her hiking boots, her strong calf muscles as she negotiates the trail. She becomes quiet. I can tell she is struggling, digging deeper. I am incredibly proud. That’s my girl, I say silently. The fact does not escape me that her greatest ambition in life is not to be a backpacker, that she had not planned on going on this trip until my trip was cancelled, that she’d much rather be lying on a beach or riding a wave on a surfboard. She is here, quite simply, for me.

When we reach the summit, over an hour later, we take time to sit on boulders, pose for goofy pictures, and take in the scenery. Before long, though, we are beginning to cool down and have to push on. A break longer than ten minutes gives the body time to build up lactic acid which results in sore muscles. We keep moving.

After the long descent on the opposite side of the mountain we enter a forest of tall lodgepole pines. Up until this point, we had not encountered many trails bisecting ours. Once in the forest, though, we began to encounter such trails — sometimes made by animals, sometimes by cross country skiers. To stay on the trail, we had three aids. The first was a general description of the trail segment. The second was a detailed topographical map. I had learned to read topographical maps and use a compass, the previous year. I had taught myself, and while I felt fairly confident in my skills, I was still a bit shaky at times. Third, we had the green and white triangular-shaped Colorado Trail makers that we saw on occasion. Unfortunately, those trail markers were becoming increasingly scarce. We had not seen one for miles. Still, we continued confidently. I was in my mountains. I was smug. A little cocky. And loving every minute of it.

Suddenly, Scarlett froze in place. She pointed ahead. “What’s that, Mom?”

“What? Where?”

“Over there,” she whispered. “I think it’s a bear.”

The possibility of bears was very real. But actually, the possibility of mountain lions was greater. I did not share this fact. “It’s a stump, Scarlett.”

We continued hiking.

The day drew on. We stopped briefly and snacked on granola bars. As we got to our feet, Scarlett told me, “I actually like this, hiking in the mountains and everything. But the thing that I don’t like about backpacking is the backpack.” She is serious.

I laugh. “It’s kind of hard to backpack without a backpack.”

“I know. But it’d be a lot better without the backpacks.”

We continue hiking. Less than an hour later, she froze in place and pointed. “What’s that?”

“It’s a stump, Scarlett.”

As we made our way through the forest, I used that phrase repeatedly. “It’s a stump, Scarlett.”

The forest became increasingly dense. Boulders were scattered along either side of the trail. As we continued, thunder rumbled in the distance. Soon, it seemed closer and was accompanied by lightning. I begin scanning the surrounding area in search of a location to pitch the tent. There was none. Boulders were strewn throughout the forest. There was, literally, not one spot within sight that was large enough to set down my small two-man tent.

Then, thunder boomed so loud that it seemed as if the forest floor was vibrating. Lightning flashed close on its heels. “Scarlett, we need to pitch the tent.”

Then, thunder boomed so loud that it seemed as if the forest floor was vibrating. Lightning flashed close on its heels. “Scarlett, we need to pitch the tent.”

“What! Here? No way! We’re almost there, Mom. We can do it. Come on!” She knew that I had planned on pitching the tent in a meadow just outside the forest. I did not realize, until that very moment, just how frightening this woods was to her. Bears live in the woods. Scarlett continued hiking. But now, she is moving at twice the speed. I am amazed. I try to keep up. “Come on, Mom!”

Lightning flashed even closer. “Scarlett, we need to pitch this tent!”

“No. We have to be almost there.” I believe, too, that we are close, but we have no way of knowing that for certain. Consulting the topographical map would be useless. We are in the middle of a dense forest with no visible landmarks to mark our bearings.

It begins raining.

She is so far ahead of me that I have to yell for her to stop. “We need to pitch the tent! It’s raining.”

“We have raincoats.”

“It’s not the rain I’m worried about. It’s the lightning!”

“I don’t want to sleep here. Let’s put on our raincoats. We have to be close.” She is not frantic, but close to it.

We pull out our raingear and put it on, put on our backpack covers, and keep hiking. She is not running, but she could not possibly walk any faster. She continues to pull away from me, but I keep her in sight most of the time.

Several minutes later I hear her yell, “We’re here, Mom! It’s here!” I emerge from the forest to find her standing on the edge of the meadow, all smiles. Barely into the grass, we drop the packs. As lightning flashes in the sky and thunder echoes against the mountains, I bark orders and we become a team.

We have set up this tent in our living room. Stretched out in it and giggled like two schoolgirls. But, now, as the rain increased, we are all business. She does not fail me. Not once. Swiftly, efficiently, we set up the tent, pull on the rain fly, and stake them both down. As if on cue, just as I push the last stake into the ground, the sky opens up and rain begins to pelt us.

“Throw it inside! Throw it all in!” I tell her as we grab assorted gear and the backpacks and toss them into the tent. We follow quickly behind, remove our hiking boots and put them under the rain sheet, just outside the tent.

Half an hour later, we have eaten granola bars for dinner, unable to cook the Ramen Noodles that we brought. We are lying in our sleeping bags, staring at the roof of the tent and listening to the rain fall outside. I shiver, even though I am dressed warmly and I am in a subzero sleeping bag. It is merely exhaustion. I lie there, trying to stop shaking, close to dosing off, even though it is only about five o’clock in the afternoon.

“What are we going to do?” Scarlett asked, pulling me out of my drowsy state.

“This is pretty much it.”

“Are you serious?”

“You can go outside and play in the rain if you want to. I’ll be in here.”

She is quiet for a few moments. Finally, she says, “Well, this is a waste of a night!”

I am not sure whether it is exhaustion, or her delivery of the line, but I burst out laughing. Soon we are both laughing uncontrollably and wiping tears from our eyes.

We spend the next four hours lying in the tent, guessing what each other’s favorite things are, and talking. We talk about pizza, which she is craving; school; her dad, my first love, who was killed years ago in a motorcycle accident; past family vacations; her sister; her brother, and, yes, the current boyfriend. She tells me that she thinks they will be together forever, that she knows it in her heart. I do not say that I do not believe that they will be together forever, that I know it in my heart. At that point, he had been almost a daily fixture in our house for over a year. And when he would leave for the last time, less than three months later from that night in the mountains, Scarlett and I would hold each other and cry and I would whisper to her, “Let him go.” But then, that night in the tent, anything in life was possible, and I wanted to be wrong. I wanted her to be right. Many years later, she would find her happily ever after; but it was not with him.

The next morning was cold. We quickly packed the still damp tent and all of our gear into the backpacks and began walking.

“I don’t feel all that well,” Scarlett told me soon after we had started hiking.

“That’s normal. You’re exhausted.”

“Do you really like this? Right now, are you having fun? Don’t you feel bad?” she asked, incredulous.

“I hate mornings. You know that. I’d feel terrible if I was waking up in a bed at home. Might as well be in the mountains.”

“I don’t know. I just don’t think that this is my thing.”

“Drink some water. You’ll feel better. The first mile is always the toughest. We will stop at lunchtime and have some Ramen Noodles,” I reassure her.

Within an hour the sun is shining. We are hiking through rugged high country. The trail is easy to follow because it is the only one visible. We have not seen another person. I see a mountain lake in the distance. I remember its description from the guide book. “That’s BearLake,” I tell her.

Her eyes sweep the landscape. “Why do they call it that?”

I realize, immediately, this was a poor choice of words. Maybe, “Hey look at the pretty lake,” would have been better.

“Probably just a name,” I tell her as my own eyes scan the landscape.

We begin ascending another mountain. It is steep. We move back and forth on seemingly endless switchbacks. We are so tight against the side of the mountain that we cannot see the summit. All we can do is climb on in faith.

We stop at one point for a snack. I take the time to pull out the trail description and read it. It assures me that, after this summit, the trail continues downhill and then levels off to a “stunning alpine meadow.” I tell Scarlett that it will be, literally, downhill after this and we continue hiking. Shortly after, we take another break. We have not seen a trail marker since before BearLake, several miles back. I am starting to second guess my navigational skills. “Can’t be much further now,” I tell Scarlett.

We stop at one point for a snack. I take the time to pull out the trail description and read it. It assures me that, after this summit, the trail continues downhill and then levels off to a “stunning alpine meadow.” I tell Scarlett that it will be, literally, downhill after this and we continue hiking. Shortly after, we take another break. We have not seen a trail marker since before BearLake, several miles back. I am starting to second guess my navigational skills. “Can’t be much further now,” I tell Scarlett.

We continue, one foot in front of the other, stopping often for breaks. I try to remember where we spotted the last trail marker. It was close to where we had encountered the guy with the dog. A couple of mountains ago and many miles back. Scarlett becomes quiet again. If we are off course, we will have to backtrack to that point. And, even then, we will be unable to continue for we cannot make our pick up point in four days if we have to backtrack several miles. Our only option would be to continue to retrace our steps to the point where Eddie had first dropped us off, and then hike into Leadville, many miles away. I had my cell phone with me, but, for the most part, cell phones are useless in the mountains. The previous year, during our entire hike, Jeanne and I had no signal. During this trip, I have checked my phone a few times and there has never been a signal.

After an interminably long time, we made it to the summit. We paused briefly, drank some water, and began our downhill descent. But not for long. We began to ascend another mountain.

“I thought it was downhill from here,” Scarlett says. She has not said much, but I wonder if she is now questioning my navigational skills too.

“Well, more or less downhill.” We continue upward. Definitely upward. We are ascending another mountain. Scarlett calls for a break and I pull out the topographical map. The trail description is wrong. The topographical map shows the trail is downhill, but not until we ascend another mountain. I scan the horizon and look for a high peak to orient myself on the map. I find one and consult the map. I study it carefully. We were supposed to have passed over a creek. We did not. But that is not unusual. During the summer, many mountain streams dry up, making finding water increasingly difficult. I look at the topographical map again. I think we are on the trail. I look at my daughter, sitting on a boulder and taking a drink from her water bottle. We are ready to hike up another huge mountain. If I am wrong and we discover, somewhere on the other side of the mountain, that we are off trail, I am going to have to ask her to turn around and climb these same mountains again to find our way back. I pause, slowly fold the map, and put it back in my backpack. I take a deep breath. “We have to climb this mountain, and then it will be downhill.”

Wordlessly, Scarlett gets to her feet, hands me her water bottle so I can slip it back into her backpack (we can each reach our own water bottles, but it is always awkward, so we always do this for each other). She gives me the faintest of smiles, and takes the lead.

“Once we’re off this mountain, then we’ll be back in the trees,” I reassure her. We have been hiking for hours in the sun. Her hopes of getting a little sun have been realized beyond her expectations. She has been applying sunblock and she is wearing the baseball cap that she swore that she would never wear but I made her bring anyway.

Our destination for the day is a meadow that, according to my planning, is just beyond the forest on the other side of the mountain. I had planned to be off the trail by four. It is now two o’clock. Despite the rugged conditions, we are making good time. Scarlett has maintained her pace, although it has become apparent that it has become increasingly difficult for her to do so. She is barely speaking now. She tugs at the straps on her backpack often, and has asked me a couple of times if my shoulders are sore, if my back hurts. I ask her, at one point, if she wants to lighten her load and transfer some stuff from her backpack to mine. Her answer is a short and indignant, “No.”

When we reach the summit the views are breathtaking and vast. For 360 degrees, we are, literally, in a mountain panorama. We stand on the summit, the sun shining, the wind strong and blowing both of our hair. We smile at each other. I am swept with emotion at the sight of Scarlett in backpack gear. Like that night in the mountains with Jeanne when I was looking at the stars, I know, at that moment, that I am living a moment I will remember. In a few seconds, we will turn, and keep hiking and that moment, that single magical moment will be broken. I blink away tears and laugh. Scarlett laughs too. We turn and she takes the lead. Soon we are traveling on the side of a mountain slope. The wind is strong and blows downhill, against our sides as we hike. We lean uphill, place our boots carefully, for if we fall here, there is nothing to break our fall — just an impossibly steep slope that continues miles below into the valley. If one of us fell, all the other could do is watch and then continue hiking out. There would be no way to navigate the slope.

“Watch your step,” I tell her. “Keep your eye on the trail.” It seems like a ridiculous piece of advice, but the surrounding mountains are so stunningly beautiful that it would be easy to be seduced by the view and stumble on the loose rocks along the trail.

Scarlett looks to her left, down the treacherous steep slope, and into the rocky valley far below. “What if we fall?”

“Don’t.”

“But what if we did?”

“We’d be dead. No doubt about it.”

She looks down again. “We would be, wouldn’t we?”

“Yep.”

We continue hiking.

When we enter the forest a short time later, I still do not see a marker. Trail markers are scarce on the trail, in keeping with the low impact philosophy of such a trail. In addition, markers are often stolen by hikers for souvenirs. Right now, there is nothing that I would rather see than one of those green and white markers. Through the woods, we see an occasional blue marker for some cross-country ski trail, which does not boost my confidence.

When we enter the forest a short time later, I still do not see a marker. Trail markers are scarce on the trail, in keeping with the low impact philosophy of such a trail. In addition, markers are often stolen by hikers for souvenirs. Right now, there is nothing that I would rather see than one of those green and white markers. Through the woods, we see an occasional blue marker for some cross-country ski trail, which does not boost my confidence.

We stop for a break, and, for the first time, Scarlett removes her backpack. “Your back doesn’t hurt?” she asks me. “I think something is wrong with my back.”

I examine her back. She is simply having pain between her shoulders from carrying the weight. I tell her that.

“No. I don’t think that’s it. It’s like a knife. You don’t understand.”

“You’re just not used to carrying this much weight. You didn’t have long enough to train. I’ve been training for months.”

“Maybe there is something wrong with my backpack, with the way it fits.”

I repack her pack, making certain the heaviest items are at the bottom of the backpack, close to her lower back. We make some minor adjustments to the straps. She tells me it is better, but I know that it is not. She is in intense pain every moment, and probably has been for hours.

As we continue, I think about stopping right there and setting up the tent. She needs rest. The site I have chosen for the night, in the meadow, is near water. We are low on water, but we should have enough to cook with if we stop now. The problem is, I am still not one hundred percent certain we are on the correct trail. If we are, we could pitch the tent here for the night and then continue to the meadow in the morning where we could get water. If we are on the wrong trail, there is no way of knowing how far the next water source is. It could be just ahead, or, literally, miles away.

“Hook your thumbs under your shoulder straps and pull forward. That will take a little weight off of your back,” I call ahead to Scarlett. She does so, and tells me that it helps. I do not believe her.

She says nothing now. Still in the lead, she maintained her pace, but was looking directly down at the trail, as if in concentration, totally oblivious of her surroundings. I asked her, occasionally, if she is okay. She says yes and continues.

I call for a break and tell her we should stop and set up the tent. We still have not seen a trail marker.

“The meadow has to be close,” she tells me.

“Unless we’re on the wrong trail.” She has seen the blue markers, too. I know that the thought must have crossed her mind.

“Do you think that we are on the wrong trail?” she asks.

I pause before I answer. I go over the topographical map in my head. I think about my relative lack of experience. I look ahead at the trail as it disappears into endless trees. I sigh deeply. “No. I think we are on the Colorado Trail.”

“Then, let’s keep going,” she says without question. This is a girl who argues with me when it’s fifteen degrees outside and I tell her to wear a coat.

“I could be wrong. And you don’t look so well.” She did not. She looked pale, even with the sunburn.

“Let’s keep going. The meadow has to be close.” She turned and continued walking. I follow. She walked with her head down. She is in obvious pain, but she is actually gaining in speed. She is determined to make it to that meadow. It is not until several days later that she tells me during this entire time, she is silently praying, “Please God, please let me make it. Please, God, please let me make it.”

“Let’s keep going. The meadow has to be close.” She turned and continued walking. I follow. She walked with her head down. She is in obvious pain, but she is actually gaining in speed. She is determined to make it to that meadow. It is not until several days later that she tells me during this entire time, she is silently praying, “Please God, please let me make it. Please, God, please let me make it.”

I follow her and decide that once we reach the meadow I am going to check for cell service. If we are on the Colorado Trail, I know there is a rough forest service road close to the meadow. Perhaps my phone will work. If not, we will sleep in the meadow tonight and I will study the map to see where the forest service road connects with a real road. I need to get Scarlett out of the mountains, one way or another.

Almost an hour later, we see a wooden sign on the edge of a meadow. The words, Colorado Trail, are carved into it. We laugh and exchange high fives. I pull a disposable camera out of my pack and snap a picture of Scarlett standing by the sign. I know, even if she does not, that it is the last picture that I will take of her on our hike. I hand her the camera, we switched places, and she took a picture of me.

We walked to the edge of the meadow near some boulders. Both of us drop our packs and drink from our water bottles. I pull out my cell phone and turn it on. Unbelievably, for the first time in two backpacking trips to the Rockies, I have a signal.

Before I say a word to her about getting off of the trail, I know she will fight it. I go over the arguments in my head before beginning. “I have a signal. If I can get in touch with Eddie, I’m going to have him come and get us,” I tell her.

Her mouth fell open. She was absolutely astonished, and, an instant later, defiant. “No. No way. We’re not getting off the trail.”

“Scarlett, you’re in pain. You don’t look well. You need to get off the trail.”

“I’m not doing it. I won’t! We’ve only been out here one night.”

“Scarlett, it wasn’t my intention to torture you. I wanted to bring you to the mountains, just you and me. We’ve done that. Didn’t we have fun last night in the tent?”

“Yeah, but…”

“What difference does it make if it’s one night or four more? We’ve hiked. We’ve seen beautiful mountains. That’s what I wanted, and that’s what we’ve done.”

Her eyes filled with tears. I can feel her argument weaken. I’m making sense. She can see it. “Mom, this is so wimpy.”

“No, Scarlett. Not at all. You didn’t have a chance to train like I did. We can come back next year if you want to. After you’ve had a chance to train.”

“This is so stupid. I don’t want to go.”

“I know. But it’s not your choice. It’s mine. And we’re leaving.”

She says nothing.

“If I can get in touch with Eddie, we can be eating pizza tonight.”

She smiles at this.

“Pizza Hut,” I say.

She laughs.

I pull out the paper and started dialing the number.

“I don’t want to leave. I’m against this,” she says again.

“I know.” I keep dialing. Miraculously, I am able to reach Eddie. I give him coordinates and he tells me he is on his way. He also tells me the forest service road is very rough and it could be a while before he arrives. I tell him we will walk toward the road.

We began walking. Scarlett continued to protest, but with less determination. At one point she stopped and had the dry heaves — a sure sign of altitude sickness. I was beginning to worry. We continued to walk slowly toward the forest service road and she stopped and heaved again. She looked as if she might pass out. I decide are done walking. I hope we are close enough to the road.

“Let’s wait here,” I tell her. I worry Eddie won’t be able to find us. Scarlett sits down on a nearby boulder and says, again, that we should have continued backpacking. I remind her that she just had dry heaves. Twice.

She shrugs. “I could have kept going.” I believe her. She could have. She would have. For me.

Over an hour and a half later, Eddie arrives. We get in his truck and head out of the mountains. I am flooded with relief. The only cure for altitude sickness is to decrease your altitude. We are moving out of the mountains, albeit at a snail’s pace. I now understand why it took Eddie so long to reach us. The forest service road is a nightmare. Eddie moves forward at about two miles-per-hour, the truck jostling us back and forth as the tires drop in deep ruts and then pull back out. I worry Eddie might damage his truck. I wonder how much it will cost me if he does. He offers Scarlett a bottle of water and continues creeping forward; chatting about the dangers of altitude sickness and reassuring Scarlett that it was, indeed, time to get off of the trail.

When he drops us off at our hotel I give him a generous tip. But it doesn’t seem enough. How could it be? I thank him profusely. Embarrassed, he nods and gets back into his truck and heads home.

Later that night, close to our hotel, we eat pizza. Scarlett is feeling better and I am relieved, to say the least. We stay in Colorado for a few more days — relaxing, shopping, and enjoying our time together.

On the way home, we stop at a gas station just beyond the Colorado state line. At the counter, there are some hamburger-shaped candies. Scarlett picks one up and asks the surly man behind the counter, “Are these supposed to be hamburgers?” He frowns at her and does not answer. I look at her in question. What else would they be? They look exactly like hamburgers.

I hand Mr. Surly our purchases and he rings them up without a word.

Scarlett hitches up her pants, reminiscent of Barney Fife. “Yep,” she says and then sniffs. “We just got off the Colorado Trail.”

We look at each other and both crumble into hysterical laughter. The man behind the counter scowls at us and hands me my change. I take it and we turn and hurry toward the exit, laughing uncontrollably. We pass a couple of customers in the parking lot and they turn to watch us, probably wondering if we have lost our minds. Both of us are hysterical. All we can do is laugh and wipe tears as we walk toward the car. We get inside, still laughing and barely able to talk. I pull out of the parking lot and we are soon headed east. Toward home. The Dixie Chicks sing Cowboy Take Me Away, and both of us sing along, the mountains fading in my rear view mirror.

This story originally appeared in Ms. Adventures in Travel: Indie Chicks Anthology

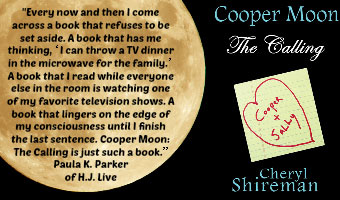

Cheryl Shireman is the bestselling author of several novels, including Broken Resolutions, the Life is But a Dream series, and the Cooper Moon series. She is also the author of ten books for toddlers including the eight Let’s Learn About series focusing on different animals and I Love You When: For Girls and I Love You When: For Boys.

Leave a Comment