I grew up at Mile Marker 84, just off the Indiana Toll Road. Or at least, that is how my Dad always described the location of our home whenever anyone asked where we lived. Other people might have mentioned our home town or street address, but my Dad thought in terms of mile markers.

My Dad was a truck driver. I write that in utter pride. Some of my happiest memories of my dad involve a semi-truck. As a very small child, before school age, I remember being impressed by the enormity of the truck my dad drove. It was huge. I was so proud that my father could drive something that seemed so big to a small child. As I looked at other objects, the semi-truck always seemed larger. I started asking about the size of other objects. “Is Dad’s truck bigger than that?” I would ask as I pointed to a car or a tractor or some other object worthy of comparison. “Yes,” was always the answer. I loved that. One day, as we approached a train overpass, I spotted a train on the tracks and began to ask mother that now familiar question. “Is Dad’s truck…?” Before I could finish the question, my mother answered, “No, your Dad’s truck is not bigger than a train.” I remember frowning as we drove under that train overpass. How dare that train be bigger than my Dad’s truck? I quickly discounted it. A train might be bigger, but a train had to stay on the tracks. It couldn’t go wherever it wanted like my Dad’s truck. From that moment on, I secretly resented trains and did my best to ignore them.

Whenever I could, I rode along with my Dad on his long-distance hauls. I rarely saw another child with their father. On the rare occasions when I did see another child, it was always a boy. In all the years I rode along with my Dad, I never saw another girl in a semi-truck. I have to admit, I liked that. While on the road, we always ate at truck stops. In those days, there were special areas that were marked “Truckers Only” and I always felt special walking into those areas holding my Dad’s calloused hands. The other truckers always smiled at me, probably missing their own children. Inevitably, for breakfast my father ordered oatmeal and toast or eggs, sunny side up. I always ordered a hamburger and chocolate milk. “For breakfast!” the waitress always asked in astonishment. My dad would shake his head and say something like, “I try to tell her she needs some eggs and bacon, but she won’t listen.” He acted as if it upset him, my breakfast choice, but I think he enjoyed his daughter’s streak of independence.

One of my most exciting “on the road” memories involves the Pennsylvania Turnpike and a pack of cigarettes. This was when CB radios were at their most popular and all of the truckers communicated with each other on channel nine. While heading east, my Dad heard the voice of another trucker he knew. Soon, the other trucker was driving behind us and both men were talking back and forth over the CB. The other trucker had his son with him. As the men took turns passing one another, both determined to be in the lead, I tried to get a glimpse of the boy, but it was too dark to see much more than a profile.

At one point the other trucker said he was out of cigarettes. My father had a solution. He had an extra pack of cigarettes on the dash. He’d simply pass them over. Through the window. From semi to semi. While driving seventy-miles-per hour down the Pennsylvania Turnpike. I remember the wind whipping through the truck, as Dad rolled the window down. It was dark outside. Inside the truck, the glow of the dash lights lit my father’s face as he smiled and stretched his arm out the window toward the other truck, always keeping one eye on the road. I could see the boy now, and he had his arm stretched out too. He was older than me, maybe even a teenager, and envied him. I wanted to be the one who was stretched out that truck window to grab those cigarettes.

At one point the other trucker said he was out of cigarettes. My father had a solution. He had an extra pack of cigarettes on the dash. He’d simply pass them over. Through the window. From semi to semi. While driving seventy-miles-per hour down the Pennsylvania Turnpike. I remember the wind whipping through the truck, as Dad rolled the window down. It was dark outside. Inside the truck, the glow of the dash lights lit my father’s face as he smiled and stretched his arm out the window toward the other truck, always keeping one eye on the road. I could see the boy now, and he had his arm stretched out too. He was older than me, maybe even a teenager, and envied him. I wanted to be the one who was stretched out that truck window to grab those cigarettes.

It seemed dangerous and exciting. And it was. First, the trucks had to be traveling at exactly the same rate of speed. No small feat in itself. Then, the trucks had to pull close enough so that the handoff was possible. Now, when I think of how close that is I am amazed that they even thought it would be possible. How long is the average arm? Three feet? The boy was leaning a bit of his upper body out the window, so let’s be generous and say he had a reach of four feet. Math has never been high on my skill list, but even I can add three feet and four feet and come up with seven feet. That’s seven feet between two speeding semis, each pulling a fully loaded semi-trailer.

So, seventy miles an hour, in the middle of the night, somewhere along the Pennsylvania Turnpike, two semi-trucks moved in unison, mere feet between them, as a package of Lucky Strikes was passed from truck to truck. Later that night, we met with the other trucker and his son at a truck stop for a meal. It did not occur to me until many years later that they could have just waited and handed off the cigarettes during that meal. I wasn’t sure if they were crazy or incredibly cool. I’m still not.

My dad drove a flat-bed trailer, which meant every load had to be chained down and secured to the trailer. This was accomplished by throwing huge chains up and over the load, hoping they would make it over the top of the load and dangle down where they could be reached and then hooked to the other side. Every chain had a hook on each end. One end of the chain would be hooked to one side of the trailer and the other would be ratcheted down with a special tool that tightened the chain against the load. It was demanding work. The chains were huge and heavy. I remember watching in awe as my Dad threw the chain high up onto the load. Sometimes they would not fall down the other side and I would crawl up on the load and push the chain over to my Dad waiting below. I also put protective plates of L-shaped iron under the chains at the top of the load on either side, so the chains would not cut into whatever we were hauling when tightened. Whenever we chained the truck down, I was up there on top of that load helping my Dad.

Except for one unbearably hot and humid summer day in Texas. The temperature was well over 100 degrees, and the humidity was so thick that it was difficult to breathe. It was the middle of the day and my Dad was chaining down the truck. I wanted to help, but he wouldn’t let me. I sat in the truck, watching him through the large mirrors that were on either side of the truck. The truck was idling and the air conditioner was on. He was wearing his normal white tee shirt and blue jeans. His tee shirt was soaked and his jeans were dark with sweat. Worried about him, I got out of the truck to offer my help. He told me to get inside the truck and stay there. I did. I watched his every move through the mirrors. Throwing the chains up and over the load, getting up on top of the load to place the L-shaped protective iron plates, and then ratcheting the chains down until they were tight. Once in a while, he’d lean against the trailer, looking as if he might pass out. He kept moving, though, and eventually finished, getting into the cool truck, soaking wet and exhausted. While I waited inside the air-conditioned truck. I felt guilty. But I also felt very loved. And protected.

As I became a teenager, boys and friends took precedence over road trips and I spent less and less time in the truck with my Dad. I don’t remember why, but one day in my early teens my Dad was supposed to pick me up at my junior high. It was a large school and as I stood outside waiting for him, teenagers flowed out the doors and toward the school buses that were waiting in the parking lot. I didn’t see his car and started to worry that he had forgotten about me. I wondered if I should get on my bus. But then I heard that familiar rumbling of a diesel and the shifting of gears. I looked up and spotted that semi coming down the road. Before my Dad had left home that afternoon, my Mom warned him that I might be embarrassed if he showed up in the semi. “Nah,” he said. “She’ll love it.” He was right. I did love it. I ran to that truck, to my Dad, with a huge smile on my face. As we pulled out of the parking lot, I asked him to honk the horn. He did, and that air horn never sounded sweeter. Or louder.

My Dad has since retired. He now drives a car, not a semi. He put well over a million miles on the road, and I was beside him for some of those miles. Now, when I travel, as I see other semis on the road, I am flooded with all of those memories. Sometimes I want to wave to the drivers, because I know how lonely they get. But as a woman, no longer a little girl, that’s probably not a good idea. I’ve actually toyed with the idea of making a sign and putting it in the back window of my car – Proud Daughter of a Truck Driver. Then, perhaps, I could wave at them and they would understand.

My Dad has since retired. He now drives a car, not a semi. He put well over a million miles on the road, and I was beside him for some of those miles. Now, when I travel, as I see other semis on the road, I am flooded with all of those memories. Sometimes I want to wave to the drivers, because I know how lonely they get. But as a woman, no longer a little girl, that’s probably not a good idea. I’ve actually toyed with the idea of making a sign and putting it in the back window of my car – Proud Daughter of a Truck Driver. Then, perhaps, I could wave at them and they would understand.

And perhaps that is exactly what I am doing now. Perhaps this is as close to that sign as I will ever get. Proud Daughter of a Truck Driver.

This story first appeared in Memories of Mom and Dad: An Indie Chicks Anthology

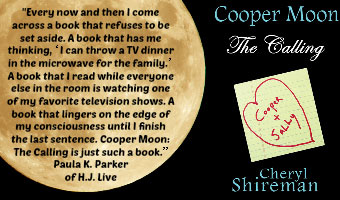

Cheryl Shireman is the bestselling author of several novels, including Broken Resolutions, the Life is But a Dream series, and the Cooper Moon series. She is also the author of ten books for toddlers including the eight Let’s Learn About series focusing on different animals and I Love You When: For Girls and I Love You When: For Boys.

[signature]

I love this. I read this today in the memory of your dad (uncle Skip ). I love your dad very much. RIP Uncle Skip you will be missed but never forgotten.

Is there any way I could get a copy of this?

Thanks Rebecca. It is from a book titled Memories of Mom and Dad. Here is a link to it on Amazon – http://www.amazon.com/Memories-Mom-Heather-Marie-Adkins-ebook/dp/B0080SNX62

I love your dad (uncle Skip).you will be missed but never forgotten.RIP you will always be in our hearts.

I was that little girl but in a freight liner. Oh how I miss my daddy. 27 years was not long enough with him.